June 9, 2014

TOP of North America climbed from "sea2TOP2sea"

Noe says: "Well done! Sea to TOP to Sea in a total of 30 days travelling climate friendly."

Noe says: "Well done! Sea to TOP to Sea in a total of 30 days travelling climate friendly."

More pictures here!

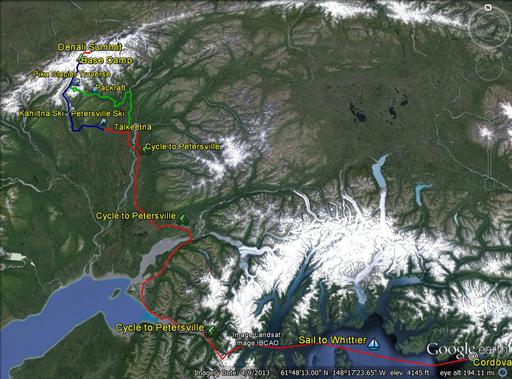

After sailing into Prince William Sound and Whittier Harbor we hiked Portage Pass, cycled over the frozen Portage Lake and further to Anchorage and Talkeetna and Kroto Creek near Petersville and back to Whittier (see previous reports).

After sailing into Prince William Sound and Whittier Harbor we hiked Portage Pass, cycled over the frozen Portage Lake and further to Anchorage and Talkeetna and Kroto Creek near Petersville and back to Whittier (see previous reports).

We visited approx. a total of 3000 students on the way towards Denali.

TOPtoTOP clean-up with Bartlett High School

TOPtoTOP clean-up with Bartlett High School

Dario sleding up to 14000 camp

Dario sleding up to 14000 camp

up the Head Wall

up the Head Wall

Dario and Martin on the TOP

Dario and Martin on the TOP

From the point we stopped cycling, we skied up the whole Kahiltna Glacier to Base Camp in 5 days and have been on TOP of America 12 days after. We reached the top on the 23rd of May, 3 p.m. and learned that only 5 climbers made it before us this year.

20h down Kahiltna Glacier

20h down Kahiltna Glacier

We climbed the same day down to our camp at 14000 feet and skied the next day for 20 hours through the night to little Switzerland. This because the snow was pretty bad and so the crevasse danger high on the lower Kahiltna Glacier. We did not continue on the Kahiltna like when we walked in. Instead we went up Pika Glacier, a side arm of the Kahiltna, and towards Excit Pass. Many thanks to Paul dropping us some pack rafts.

Granit Glacier

Granit Glacier

From Pika we went over Exit Pass, Granit Glacier, Wild horse Pass and Wild horse Creek to the Tokositna River.

Camp on the Tokositna River

Camp on the Tokositna River

Rafting out on the Tokositna River we reached Talkeetna on the 28th of May, 5 p.m.. warm welcome in Talkeetna

warm welcome in Talkeetna

Personal report from Dario:

Surrounded by friends

Surrounded by friends

The biggest challenges for me was to get through the dense forest (willows) to access and leave the glaciers on the walk out. I start thinking that all this small trees love me and like to hug me. Like this it became fun. The coldest was on top, but I felt much colder at the beginning cycling from the ocean to Denali and at the end of the trip pack rafting nearly 2 days in this icy water.

I used my pack raft as a tent to safe weight on the walk out:

I used my pack raft as a tent to safe weight on the walk out:

The best for me was not the TOP. I liked the slow transmission from the beach, forests, tundra, lower glaciers up into the alpine region and back. For me it is the right way to climb a mountain, starting at the ocean. It comforts my soul. It was a honor bringing the remains (ashes) of my friend Daniel and Karl (Ron's sun) to the top. - But the very best was to see my loved wife and children again after the TOP and to continue the expedition again, together as a family:

The scariest moments where when Martin nearly got hit by rock fall, Odin didn't attached his sled and the sled torpedoed down the mountain for about 2000 feet; - luckily not ending in a crevasse and Dana unfortunately getting sever diarrhea. One rucksack with valuable equipment got probably stolen ...let's hope for a miracle.

camp before the summit - all in one 3-men-tent!

camp before the summit - all in one 3-men-tent!

I believe we were successfull thanks to the good team, equipment and friends. Many thanks to all the people supporting us, specially: Willie and Ellie Prittie, Chuck Homestead, Paul Roderick, Rayna Swanson and David Wigglesworth, Brian Okonek, Werner Rauchenstein, Ron Anderson, Higman Bretwood, Mark Cohen.

our camp at 11000 feet

our camp at 11000 feet

Back on the sailboat Pachamama, Sabine,Peter and I climbed Mount Mc Kinley Peak near Cordova. Sabine kayaked with me the first leg from the sea towards the peak earlier this year against a storm. We were happy to climb another Mount Mc Kinley from Sea to the TOP and back together :-).

Back on the sailboat Pachamama, Sabine,Peter and I climbed Mount Mc Kinley Peak near Cordova. Sabine kayaked with me the first leg from the sea towards the peak earlier this year against a storm. We were happy to climb another Mount Mc Kinley from Sea to the TOP and back together :-).

What's next:

We are now back on the expedition boat Pachamama and continue to clean up the world and to inspire more young people to protect the planet; - collecting top-examples for the environment and act on the way to the next TOP.

We are now back on the expedition boat Pachamama and continue to clean up the world and to inspire more young people to protect the planet; - collecting top-examples for the environment and act on the way to the next TOP.  Andri and Alegra cleaning up Cordova Harbor

Andri and Alegra cleaning up Cordova Harbor

Personal report from Peter:

Peter on the West Buttress

Peter on the West Buttress

It was not an easy decision for me whether or not to join the TopToTop expedition team climbing Denali. On the one hand it was a great, exceptional opportunity for me to do something really demanding and adventurous. On the other hand I was not sure whether I could meet the high demands posed by the highest mountain in North America and how to deal with the extreme weather conditions I would probably experience up there. I felt that I would decide against a climb if I were to read and think in detail about the risks and dangers of such an endeavor. So I let my heart decide and it simply said "go for it".

In retrospect it was the right decision. I didn't reach the summit, as the conditions were tough on the only possible day to go up to the very top of Denali - and this time I let my brain decide, and it came to the clear conclusion that it was too risky and demanding for me under the given conditions. But the two weeks on the mountain were very rewarding for me despite not summiting. I learnt that my fitness, which has seen better days, was still good enough for the long ascent and the heavy loads of equipment I had to carry up the mountain and my health was able to deal pretty well with the stress due to acclimatizing to high altitudes. Another experience was that the cold was less of a problem than what I expected. The excellent material from Arc'Teryx certainly helped a lot, and the group as well: four people in a tent designed for three kept as pretty warm during the coldest night at 17,200 feet while heavy winds made the snow walls around our tent collapse.... And, last but not least, the constant support by all the team members helped me a lot to overcome minor problems so that I felt free in my mind to enjoy again and again the great wilderness of the Denali area.

Personal report from Martin: Climbing to the TOP

Martin at camp 14000

Martin at camp 14000

On Monday, May 11 the five Top to Top team members arrived in Denali base camp at 7200 ft (2200 m). We had spent time getting to know each other in Cordova where the Pachamama is currently docked. The team for this leg of the Sea to Summit journey consisted of Dario, Dana and I, who had previously skied to Denali base camp, and two additional members, Peter and Odin. Peter and Dario go way back and have climbed together in Switzerland and the Himalayas, and Odin is a good friend from Juneau, Alaska.

Before we had our mandatory briefing at the Talkeetna ranger station, where we mostly discussed the clean mountain ethic that is now the norm on Denali as well as the west buttress route, which we would be climbing. On Denali all human waste is considered hazardous material and has to be disposed of in deep crevasses. To facilitate this process we were issued two Clean Mountain Cans (CMC's). A CMC is basically a small bucket with a tight fitting lid into which you can poop. A biodegradable bag makes the poop easier to dispose of (Not too easy though! More on this later). Above Camp 3 at 14000 ft (4300 m) all waste must be kept and transported lower on the mountain, as the crevasses at this altitude are no longer suitable for waste disposal. Despite the many drawbacks of pooping in a bucket, CMC's are actually really great as at any given time there are hundreds of climbers on the mountain, which would create quite the sanitary problem without the cans. Chris, the ranger who gave us our briefing, also had lots of good information (and some not so good...) on the route from base camp to Talkeetna, which is seldom traveled and can be difficult without good local knowledge.

Arriving in base camp was much different than when Dario, Dana and I were last there. Previously, base camp was nothing but our tent and our equipment. Now, it was a bustling tent city with a permanent air taxi representative, park rangers and dozens of other climbers. Luckily Mt. Hunter was still just as impressive. We didn't waste any time and immediately skied up to Camp 1 at 7800 ft (2400 m) with our heavy sleds. Hauling five people's gear for a 20 day climb on a cold, high altitude mountain like Denali is no easy task. We had a plethora of equipment including snow shovels, a mountain of food, 11 gallons (42 liters) of fuel, ropes, cooking equipment, tents and all the personal gear associated with a big mountain climb. This first day above Base Camp was just a taste of what would await the next day, when we would ski from Camp 1 at 7800 ft to Camp 2 at 11000 ft (3350 m).

The next day we set up a cache to lighten our loads a bit, as we would need about three days of food to Ski from Camp 1 down to the Pika glacier, where TAT would take our skies and bring us our packrafts after the climb. This was a long day as we were skiing with full loads (~110 pounds per person) up the last section of the Kahiltna glacier. We experienced for the first, but not last, time the frustrating process of skiing behind groups that are traveling at a slower pace. Passing a roped team of four to five climbers is no easy task while hauling gear uphill. We made good time and reached Camp 2 in the early afternoon. One of the few benefits of having so many climbers on the mountain is that you can often find a camp site that has been prepared by another group. On Denali the snow is perfect for cutting out igloo blocks. This is a good thing, because the weather is extremely unpredictable in these northern latitudes. Throughout our climb, wherever we set up a camp we would build high snow walls around our tents and cooking area to protect us from the strong winds. On many occasions these walls saved us from having serious problems with our tents. We planned on occupying Camp 2 for at least two nights to begin the acclimatization process, and the hard work of building walls served a dual purpose by helping us acclimate as well. The more you work at altitude the faster the acclimatization takes effect.

Day 3 would be our first excursion to Camp 3 at 14000 ft (4300 m). We were all excited to begin climbing as Camp 2 was the highest that we would ski on this trip. Peter decided to stay behind so Dario, Dana, Odin and I set out in two teams up 'motorcycle hill'. Odin informed us that motorcycle hill was where the old climbers used to stash their motorcycles. This was before motorized vehicles were banned on Denali of course... we were not impressed by his 'local knowledge'. After the steep but very easy to climb motorcycle hill came 'squirrel hill', which was a bit more exposed and quite icy on this trip. At the top of squirrel hill the wind hit us and we realized that this would be quite a cold day. The higher we climbed towards Camp 3 the faster the wind blew. At the aptly named windy corner it started to get pretty cold with a wind chill of at least 20 below. By the time the four of us reached 14000 ft we were all (maybe not Dario...) feeling the altitude and were cold. We quickly dug a cache to stash the food and fuel that we had brought up and got out of there as fast as possible. It was a treat to return to Camp 2 and have a hot meal and some water. None of us slept much that night as the wind had moved down to Camp 2 and was shaking the tent furiously, even with our nice snow walls!

Day 4 was another cache day up to 14000 ft. Squirrel hill was much less icy as the sun was shining brightly and made the snow quite soft. This was good for our feet, but the heat was brutal. We applied sun block constantly, but I still got burned pretty badly. We found another camp site with partially built walls at Camp 3 and set up a tent so that tomorrow we could move up to Camp 3 permanently. The views that we had of Mt. Hunter and Mt. Foraker were absolutely amazing from Camp 3. Our descent back to Camp 2 was great in the heat of the sun and we literally ran down the mountain, reaching Camp 2 only 38 minutes after leaving Camp 3! Not bad considering the climb up took us close to four hours. I did have my first close call on the mountain when I narrowly dodged a rock at windy corner that would have knocked me off my feet. This served as a good warning for us, and thereafter we always hiked past windy corner as fast as possible.

Dario woke us at four in the morning on Day 5 for an early start up to Camp 3. We brought everything with us and were settled in at Camp 3 with 10 days of food and fuel by noon. Our afternoon was spent preparing for a storm that was forecasted to arrive the next day. The walls around our tent and our excellent cooking area were steadily growing higher and higher, which would serve us well during the coming days. Our nearest neighbor was a Mongolian woman who was attempting to climb Denali for the second time, solo. She was obviously very tough and had just returned from high camp at 17000 ft (5200 m) where she spent two days waiting out a storm before climbing down in high winds.

We spent the next day reinforcing our walls along with the rest of the climbers at Camp 3. Word about bad weather spreads quickly through camp and Camp 3 was starting to resemble some kind of fortress with all the snow walls that were being built. Somehow we misplaced, or another party 'reappropriated', one of our snow shovels. This was not a good situation because my shovel broke as well, and we were only left with two shovels at Camp 3. This was not enough because we needed at least two at Camp 4 as well. Two of us would have to return to Camp 2 to grab another shovel that we had stashed there. Odin and I volunteered for the task, but it was already too late in the day to do anything so we would wait.

We had now been on the mountain for a week, and we were beginning to acclimate quite well to the altitude. Odin and I hiked down to Camp 2 and back up to Camp 3 within a four hour time period and were barely winded, which was a good sign for the rest of the climb. When we returned to Camp 3 it was clear that something was wrong. Dana was still in the tent and one of the CMC's was far from clean. It turned out that he had some digestive problems, possibly associated with contaminated snow. He was in bad shape and we had to go get some advice at the medical camp that the park service maintains for just such occasions. The park service said that they would keep Dana overnight on oxygen, as he was also having some problems acclimatizing, and inform us in the morning about our options.

In the morning he was still hurting, though the digestive issues seemed to have subsided a bit. It was clear that he couldn't climb any higher in his current state, and the rangers advised us to bring him back to base camp for evacuation. We were all a bit apprehensive about leaving our camp at 14000 ft because of the large amount of gear that we had there. We decided that two of us would escort Dana to base camp and two would stay with the gear at Camp 3. Odin and I volunteered for the task. We both thought it might help with our acclimatization to sleep at lower altitudes for a night or two, and we also wanted to ensure that Dario had a chance at the summit if at all possible. Once the decision was made we immediately set out for Camp 2. Dario short-roped Dana from Camp 3 to Camp 2 and then returned to Camp 3, while Odin and I strapped on our skis and began heading down the Kahiltna glacier with Dana, who was still on oxygen. It was slow going as we had all of Dana's gear in a sled and the slope was quite icy. Once we hit the Kahiltna glacier we were enveloped in a ground blizzard and conditions became pretty bad. Visibility was only 10 meters or so and the wind had scoured the glacier clean creating icy conditions. We pressed on until we reached our cache at 7800 ft where we had spent the first night. Odin and I found a hole in the snow where we would be a bit protected and set up the tent with much difficulty. Luckily the increased oxygen at this altitude seemed to have helped Dana out and we spent a relatively comfortable, but noisy, night at Camp 1.

The next morning we set out for base camp and had Dana on a TAT flight by three or four in the afternoon. We set out back up the glacier and moved right back into the same storm that we had skid down in. We were back at Camp 3 by late afternoon the next day. All told it took us only a bit over 48 hours to hike and ski from Camp 3 to base camp and back. Needless to say we were tired that first night back at Camp 3.

The weather was good and the forecast was good so the next morning we packed up and headed Camp 4. While Odin and I were retrieving the shovel at Camp 2, Dario and Peter had stashed a tent at the top of 'the headwall', which towered over Camp 3. The headwall was the most technical part of the climb so far. This 45 degree ice slope had fixed lines in order to prevent accidents. We reached the col at the top of the headwall in good time and uncovered the cache that Dario and Peter had stashed a few days ago. This next part of the climb, from the col above the headwall to Camp 4 at 17000 ft (5200 m), was my favorite section of the route. We hiked up a steep ridgeline for about half a mile with stunning views of Mt. Hunter and Mt. Foraker the entire time. It was spectacular, and exhausting. The air at 17000 was noticeably thinner that at Camp 3. We reached Camp 4 in the late afternoon and began building the usual snow wall. We had only one tent here for the four of us as we would be spending the least amount of time here possible.

The next day, Day 12, was windy and cold. The cold really began to become a factor in our daily routine here at Camp 4. We decided not to make a summit attempt quite yet because the wind was picking up. The wind chill today was 38 below zero, the coldest temperature so far. We spent a lot of time cooking water at this altitude, which involved sitting out in the cold wind. Our heavy down jackets became very important pieces of equipment.

After a miserable windy night cramped in the tent with four people we were excited to see that the weather was good. Today would be summit day, Day 13 of the climb above Base Camp. Peter and Odin decided that they would not go for the summit because of the way that they felt in the morning. Dario and I decided that we would give it a try, despite the fact that the wind was already picking up and clouds were moving in. We geared up quickly and headed out by 830 in the morning. To reach the col at Denali Pass from Camp 4 you have to climb up the most dangerous part of the west buttress route, the so-called autobahn. The autobahn and Denali Pass are where at least 80% of the deaths on Denali have occurred. It is a steep section of snow and ice with many crevasses below it. If it were not for the extremely unpredictable weather at this altitude Denali Pass and the autobahn would probably not be so dangerous, but when you add high winds and bad visibility in the danger becomes much greater. We had to follow another group up the autobahn which slowed us quite a bit, but once we reached Denali Pass we passed them and were free to move at our own pace. This quickly became the most grueling climbing that I had experienced in my life because of the thin air. Luckily the weather remained stable and we were able to make good time. At around noon we took a break, sure that we were very close to the summit ridge. We had some chocolate and some tea and set off again. As we approached the 'summit ridge' we quickly realized that we were mistaken. We still had at least a mile to go and over 1000 ft (300 m) to climb.

Finally, after what seemed like an eternity to my oxygen deprived mind, we reached the real summit ridge. We hiked along the ridge for a few hundred meters, and at 330 in the afternoon, eight hours after leaving base camp; we stood on the top of Denali at 20322 ft (6194 m). For me, as a lifelong Alaskan, this was a dream come true. It was also a very sad time, as we had brought the ashes of Odin and I's good friend Daniel to be scattered. We performed a small ceremony and sent Dan on his way, took some photos and then we began the journey home. We reached Camp 4 later that afternoon and were able to rest for a bit. I was more exhausted than I have ever felt before. We quickly realized that the weather was not getting any better so we decided to break down our 17000 ft camp and head for Camp 3 at 14000 ft. We reached Camp 3 at around 10 in the evening and had a well-deserved rest.

Our last task before leaving Camp 3 for our journey back to Talkeetna was to clean out the CMC. Somehow the plastic bag had frozen itself to the inside of the can and it was virtually impossible to remove without breaking the bag. It was a messy affair all around and Peter valiantly took the initiative and freed the bag with a few rounds of boiling water. We were all happy that soon we would be finished with the cans for good. Our ski down the Kahiltna glacier was uneventful except for one little issue. Odin and I were skiing without our sleds tied into the harness, because it is easier if you can grab the plastic poles to which the sled is attached and steer with them. A little bit below Camp 2 at 11000 ft Odin was pulling some fancy turns and fell down, while his sled just kept on going. A 70 pound sled does not stop quickly. Two thousand feet down glacier he was lucky enough to find it intact, but it was a pretty close call as he had some important equipment in the sled. Once we reached 'heartbreak hill', immediately below base camp, Peter decided that he was too exhausted to make the 100 mile journey out to Talkeetna. We capitalized on the situation and loaded him up with a huge amount of extra gear that we wouldn't need for the trip out and sent him on his way to camp, while we began what would be a grueling ski down the Kahiltna on the same route that we had travelled up weeks ago.

Martin from Granit Glacier to Wild Horse Pass

Martin from Granit Glacier to Wild Horse Pass

Personal report from Odin: Skiing-walking-rafting out

Odin arrived in Talkeetna

Odin arrived in Talkeetna

Odin's feet

Odin's feet

At about nine in the evening, Dario, Martin and I said our goodbyes Peter and continued skiing down the Kahiltna Glacier. Below basecamp, the route changes drastically: the well-trodden "superhighway" that forms the entire West Buttress route discontinues. Instead, an untracked glacier lay before us, requiring us to rope up. (We had skied unroped from 11,000' to basecamp, as the chances of a crevasse fall skiing downhill along the heavily-used main trail seemed very remote).

The topography of the lower Kahiltna glacier is generally mellow and rolling. Several miles below basecamp, we threaded our way through the crevassed terrain of a low-angle icefall. We had already dropped quite a bit of elevation, and temperatures were hovering at close to freezing. This vexed Dario. Warm temperatures meant that the snowbridges concealing many crevasses would be weaker and less likely to support our weight. Dario later said he nearly turned us back to basecamp at this point. Yet we pressed onward, passing beneath a steep mountainside along the icefall's eastern edge.

We continued skiing for a number of hours, down mellow hills, around crevasses, across large flat stretches. All three of us had long since run out of water. Finally, at about 2:30 AM, Dario let us stop so that Martin and I could cook some snow-water. We ate and drank lots before continuing on our way. Because of the snow conditions, Dario decided it was safer to descend the glacier at night, rather than camping and continuing the following day.

After several more hours of nonstop skiing, we reached the confluence of the Pika Glacier. It was now about 6:00 in the morning. We had traveled well over 30 miles since setting out from 14,200' camp the previous afternoon. The junction of the Pika and Kahiltna glaciers was a scant 4,000' above sea level. Mosses and lichens grew in patches on the steep mountainsides.

Dario thought it best to press onward a few final miles up the Pika Glacier. We donned our climbing skins and wearily dragged sleds, backpacks, and bodies up the slopes. After 18 hours of travel downhill, it was torporous skiing sleep-deprived, uphill along steep sidehills. My feet rubbed raw and painful against my wet boot-liners. My sled tracked poorly and overturned once or twice. Enraged, I yelled curses at it and jabbed it with my skipole.

At 8:00 in the morning, arriving at a flat plane where the two arms of the Pika Glacier converged, we probed out a campsite and set up our tent. Martin cooked; we gorged ourselves on couscous and fell asleep for many hours.

The Pika drainage is known as Little Switzerland because of the dramatic rock mountains and spires surrounding the glacier. The glacier's northern tributary seemed a near-perfect amphitheater walled by congruous rock teeth. Our intended route would cross a single low notch in the sheer sides of this valley: Exit Pass. Eveningtime, once we had awoken and eaten a hot meal, the three of us skied the mile or so up to the pass to investigate avalanche conditions. Dario dug a snow-pit at the top of the pass while Marin and I leapfrog-belayed eachother down the 40-degree slopes of the far side, testing snow conditions and checking the exit route for snow conditions, bergschrunds, and other obstacles. Dario commented that the snowpack was mostly weak, and then released a small wet-snow slide while ski-cutting the Pika side of the pass during the descent back to camp. The ski back down to camp was awesome, even through the late-spring mashed potatoes. I felt a bit sad that we would be getting rid of our skis the following morning.

After cooking a third hot meal, we went to bed for the night. The following morning, we woke up early, packed our camp, and skied up the main-stem (South fork) of the Pika. There, in the flats near the top, was the site where TAT would bring our packrafts and other supplies. A dense morning fog began to break shortly after we arrived at the landing zone. An hour or so later, TAT director/pilot Paul Roderick arrived, carrying our gear along with Sabine and the Schwoerers' four children, whom Paul had graciously brought along for a brief visit with Dario. Sabine carried a bag of fresh apples, oranges, carrots, and other goodies--an unexpected treat after a few weeks with no fresh fruit or vegetables.

Dario had been exhorting us to "go light" and pack only minimal equipment for our hike/packraft out to Talkeetna. We traded our skis for snowshoes and left behind much of the food, clothing, and other equipment we had dragged to Little Switzerland with us. After several days of recurring discussions, Dario finally persuaded Martin and me to abandon even our regular tent in favor of the cooking tent--essentially a lightweight nylon tarp offering no protection against mosquitoes. Despite my extreme reluctance to go tentless, Dario's advice paid off in the end. Even without a mountaineering tent, Martin's and my rucksacks weighed quite a lot. In addition to personal sleeping bags, raingear, harnesses, snowshoes, and packrafting equipment, Martin and I each carried considerable group gear, including rope, stove, pot, fuel, and cooking tent. Martin traded the climbing rope back and forth with me several times during the hike out, each of us carrying it till brink of exhaustion before handing it off to the other.

Paul, Sabine, and the four children said their goodbyes, and the airplane quickly vanished beyond Little Switzerland's rock ridges. Dario told us to hurry. It might rain he said, and if so, avalanche conditions on our second pass crossing would make travel too risky. In that case we would have to hike out to Petersville with our packrafts on our backs, a prospect that none of us relished.

We quickly packed our bags, snowshoed down the main-stem of the Pika and up its North tributary. We easily crossed Exit Pass onto the Granite Glacier. After several more miles of snowshoeing, smooth snow gradually gave way to very jagged moraine, consisting of wildly-jumbled boulder-fields fed by the crumbling mountainsides above. Travel became slow and meticulous. At one point, as Martin crossed a steep sidehill, an ice-chest-sized boulder slid away, sweeping him off his feet as it plowed downward in my direction. Fortunately it stopped after a little ways and no harm was done.

A half-hour later, we reached the base of the moraine, leaving behind the worst of the bouldery morass. Here, willows, cottonwoods, flowering plants and mosses grew among the rocks. Tracks from moose and birds were visible in the glacial silt. All of these sights were lovely after weeks of nothing but rock and ice. A short ways downstream from the moraine's terminus, we stopped and traded our clumsy mountaineering boots for sneakers, which had been included in the TAT airdrop.

A small stream fell from the mountains to our left through a steep gorge. The brushy ridge next to it marked the beginning of our climb up to Wildhorse Pass. We wove our way over some boulders, through some willow & alder shrubs, which repeatedly snagged against the packraft paddles strapped to our rucksacks. After a little while we gained the ridge, which quickly became knife-edged, with 40- and 50-degree dropoffs in either direction. It was covered with low subalpine vegetation, which can be quite slippery, and which the smooth soles of my early '90s Nike Airs were not designed to grip against. (I had found/packed the shoes at the last minute before our trip). I moved cautiously, grasping clumps of woody-stalked plants whenever I had to step onto the steep slopes on the sides of the ridge. After a climb up through a brushy gully, the ridge leveled off before dropping a short ways into a snow-covered alpine valley.

Once again, we donned our mountaineering boots. Martin and I examined two low saddles between the mountains ahead of us. We assumed that one of these was Wildhorse Pass. Yet Dario, who carried the map, led us to the base of a 45-degree snowslope rising several hundred feet up to an indistinct segment of ridgeline. It didn't look like a pass at all. But, Martin and I agreed, Dario had never yet been wrong when it came to navigation. Still concerned about avalanche potential, Dario led us to an scree-covered strip of bare ground at the edge of the snowslope. Toward the top, the slope became steeper and scree gave way to crumbly bedrock. We worked our way along a narrow ledge, sometimes grasping rock handholds and swinging our heavy packs out over the steep slope beneath us. Ordinarily, this route would have seemed like a ho-hum class IV scramble, but our heavy rucksacks and clunky mountaineering boots made the going slightly more tentative. "This is my first time rock-climbing in these boots," remarked Dario as he worked his way up the side of the rock face, near the edge of the snowpack. Rock gave way to a final fifty feet or so of snow, and we soon stood at the top of the divide, looking down at Wildhorse Creek and its broad, white valley. We lingered for only a brief moment before starting down the opposite side, but as I stood there I felt a few drops of rain strike my forehead. Although this sprinkle didn't lead to any showers just then, it seemed like a fitting sign that our hurried march that day had paid off.

We descended a scree/heather slope into the nearly-unbroken snowpack covering the valley below. The light indicated it was beginning to get late, but Dario suggested we snowshoe to down the valley to below the snowline before camping. This made good sense, as our cooking tent had no floor. So onward we trudged. I hate snowshoes and quickly began cursing them as I fell behind Dario and Martin. Tormented by my heavy backpack, I eventually asked Martin to please take the climbing rope from me. I mentioned that I needed to find some running water; instead, Dario poured me an entire litre of his.

After a few long hours slogging through the sticky snow, it at last gave way to wet, subalpine grasses and shrubs. Ptarmigans flew back and forth across the tundra, making me hungry. We decided to camp along a slightly-flat bench toward the bottom of the valley wall. A charcoal gray cloud hung in the dusky sky. I announced that I would set up the tent, but Dario advised me against this course of action: "I suggest that you do not set up the tent, but just hope that it does not rain." Despite all of my hopes, we were awoken by large raindrops at some point during the night. Martin and I fumbled around setting up the tent, while Dario laid his packraft across his body for a raincover and went back to sleep.

Morningtime it was still raining. We trudged through willows and wet meadows for a few miles. The brush gradually became thicker, and a few steep ridges pointed downward, ending near the banks of the Tokositna River. We made several meanders, trying to find a good route through the brush and steep terrain. The last few hours to the river were a familiar, southern Alaskan bushwhack: zigzagging through dense alder, ducking under branches, leaning sideways to try to avoid catching our paddles on the shrubbery.

We arrived at the riverbank sometime in mid-afternoon. Martin and I cooked a small bag of couscous, one of the only hot meals we had packed with us. It was around this time that my camera, containing all of my pictures from the trip, disappeared. We inflated our packrafts, strapped down our gear, and carried the rafts to the main channel of the Tokositna. None of us had ever packrafted before, but Martin and I had experience canoeing and sea kayaking, while Dario had worked as a rafting guide in Switzerland. The upper Tokositna is a shallow, braided glacial river with some moderate rapids and standing waves, but nothing overly difficult. Nevertheless, I managed to hit a treetip along a cut-bank, and a stump where two channels diverged. Both times I took on lots of water over my gunwales. Martin and I decided it prudent to stop and hold a brief safety meeting, while I dumped the water out of my raft.

We continued without stopping for at least six more hours. As I got used to the packraft and properly balanced my gear-load, I began to fully appreciate just how much fun packrafting is. The swift-moving glacial river gave way to slow, heavily-braided channels with swampy riverbanks and lots of small islands. From there, it opened up into a few very broad channels, where three trumpeter swans honked loudly nearby. Most of the rest of the Tokositna was a single large channel with few rapids, waves, or other obstacles. The going was pleasant, if not overly exciting. Dozens of times, beavers dove from the riverbanks into the water as we rounded bends into view.

The rain continued intermittently, and each paddle-stroke sloshed more water into my raft. The floor had long since become inundated--I was sitting in a puddle of glacial water. Although I repeatedly bailed the boat out, my ass formed the lowest point at the back of the raft, from where I could not reach all the water. I tried to remain aware of my body temperature. Sometimes I felt a bit chilly, but it didn't seem too serious. I dug some food out of my backpack, ate it, and kept paddling to try to stay warm.

At some point during the evening, we rounded a gradual bend and the river began flowing northward. It was along this northbound section, a few miles before the Tokositna flows into the Chulitna River, that a few different park rangers had told us there was wilderness lodge. "He's a real friendly guy," the rangers had said of the lodge's owner. "You can stop by and have a beer; dry off your clothes." Dario told us he would try to talk the lodge-owner into giving us a free room for the night. Late in the evening, we finally spotted an old-looking wooden house with a few outlying cabins. There was no dock, however, so we pulled up to a narrow, sandy shoal a hundred yards upstream of the buildings. As I stepped out of my raft, I noticed that my legs were having trouble moving after sitting for so long. I also noticed that all my motor movements were stiff and clumsy, that I was shivering pretty hard. Evidently I was quite a bit colder than I had thought. We walked a short ways along the top of the riverbank in the direction of the buildings. I looked over at Dario and Martin; they, too were visibly shivering. Suddenly a doubt crept into my mind: what if we spent many more minutes wandering around looking for those buildings, and then they weren't really a lodge? I was too cold to take that kind of chance. "If we don't find the lodge in about 30 more seconds," I declared, "I need to go and start up the stove." I don't even think I waited thirty seconds. I had a drybag with a dry change of clothes in my raft. I announced I was going back to change into them. By the time I had gotten the dry clothing on, Martin had gathered up dry, dead spruce branches from the undersides of some trees, and had formed them into the shape of a campfire under the trunk of a leaning birch-tree. I poured white gas over it, Martin lit it up, and I continued to forage for dry spruce-branches.

The three of us sat/stood close by the campfire, letting the flame gradually warm us back to normal body temperature. The park rangers had given us the lat/long coordinates for the purported lodge. Dario's GPS indicated it was still almost a half-mile downriver. We discussed whether or not to continue. At first, I said I was not yet nearly warm enough, but as my body warmed up, I thought of a dry, cozy bed and my mind warmed up to the idea. So we got back in our rafts and floated down a half-mile more, to the beginning of a landmark boulder-field in the river. No lodge. The building we had passed had had a "For Sale" sign on the outside of it: evidently it had used to be a lodge but was now abandoned. We set up the cooking tent on a silty shoal, and the three of us spread out our bedding underneath it. My down, -40-rated sleeping bag was so soaked it barely kept me warm at +50 Farenheight.

We awoke late the next morning and continued on our way. Each of us had only a little bit of food left, and no more water. The water from the main river seemed very suspect, even with our purification tablets, given all the beaver activity. Martin found a muddy rivulet from which we both took water, but neither of us felt inclined to drink any of it.

The sky was still overcast, but the rain had stopped. We continued on our way. The going became quicker a few miles downstream, where the Tokositna empties itself into the larger Chulitna. We stopped at the Parks Highway Chulitna River bridge, approximately mile 135. Here, there was supposedly a gas station with a convenience store. I had traveled up and down the Parks Highway dozens of times and never seen such a gas station along that section of road; yet for some reason I let myself believe that there was one. No such luck. Once again, all three of us were a bit chilly, but not nearly as chilly as we had been the previous evening. A walk up the road toward a fancy Princess Lodge was sufficient to warm us up. As we crossed the Parks Highway, Dario wished that one of the passing vehicles would happen to be a sandwich truck. But once again, no such luck. We ate the last of our food and continued on our way.

Down the Chulitna we continued, through the canyon section near the highway and again out into the flats, where the channel again became braided. Dario cautioned us to be careful, that many accidents happen at the very ends of trips. I had been thinking the same thing. Five or six miles upriver from Talkeetna, I again decided I was too cold and asked that we stop at a river-island. I took off my pants, rang them out, and jogged several laps around the small island. I folded up my sleeping pad and placed it under my seat, raising my ass above the wet bottom of the raft. This worked great--I stayed dry the last hour of the trip--and I kicked myself for not thinking to do this sooner.

Peter, Sabine, and the four children greeted us in Talkeetna at the riverbank, along with Anja, a teacher who had come from Switzerland to tutor the Schwoerers' children. Sabine had brought an assortment of food: fruit, spaghetti, coffee. We ate, visited, and took TOPtoTOP photos. I briefly jumped in the river. Dario walked the few blocks into downtown to complete the very, very last segment of his Denali trip.

Martin and I checked into our hostel, cleaned up, and the entire group met at a local pizza place for dinner, where I stuffed myself to the point of strong discomfort. The last several days of our trip had been awesome, but it felt really good to have a hot shower, warm bed, and delicious food. Odin cooking on Pika Glacier

Odin cooking on Pika Glacier

Personal report from Dana:

When Dario asked me to join the Top to Top Denali expedition last fall it didn't take me long to agree. I had played around Denali in the past but never attempted the climb, although it was something I had certainly thought about. Although I didn't know any of the other team members I feel like we quickly morphed into a well organized team. And that is the message I came away with on this climb: the power of teamwork.

The climb was going well for me for the first week but then at our 14,000 foot camp I was stricken with severe diarrhea which really incapacitated me. The others and I realized that there was no way I would recoup at this altitude. The only thing I could do was go down to base camp and fly out. My fear was that I had compromised the entire expedition and the others would have to give it up to take care of me. This is where the teamwork kicked in. Martin and Odin volunteered to accompany me down, hauling all my gear. I was so struck by their willingness to descend all that way to get me out and then turn around and climb right back up to the 14,000 foot camp. It was an incredible gesture on their part. While they got me down to base camp, Dario and Peter were able to establish a high camp so the team would have a shot at the summit.

It's seeing this teamwork and unselfish willingness to help that made this climb an incredible experience for me.

Sick Dana short roped down from 14'000 to 11'000 camp by Dario and further with Martin and Odin to BC on 7800 feet

Sick Dana short roped down from 14'000 to 11'000 camp by Dario and further with Martin and Odin to BC on 7800 feet

Sabine's film coming soon!

June 13, 2014

Denali Media Coverage

From Sea to TOP of Denali and back to the Ocean

From Sea to TOP of Denali and back to the Ocean

Listen to the KTNA radio report!

Listen to the KTNA radio report!

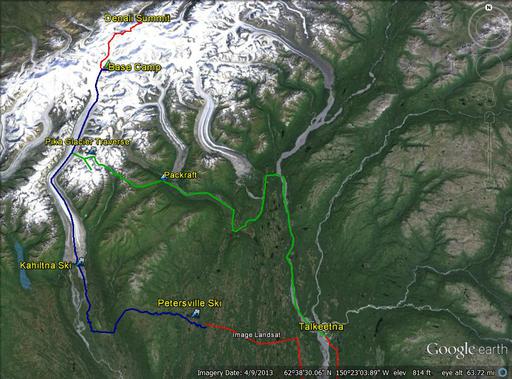

Detail map of the walk in and out

Detail map of the walk in and out

KTNA radio report:

This year, over a thousand people will try to climb Denali. Some of those will be making the attempt as part of a "seven summits" expedition, which involves reaching the highest point on all seven continents. One family expedition, named Top to Top, is attempting the seven summits in a way that has never been done before. K-T-N-A's Phillip Manning has more:

""For most climbers coming to Denali from outside of Alaska, the trip involves long hours of travel via planes and road vehicles. For Dario and Sabine Schwörer and their children, it meant years of travel by very different means, as Dario explains.

"Just sail from one continent to the other, and then climb the highest peak in each of the seven continents...Denali was actually our second-last."

To get to Denali, the Schwörer family sailed through the Panama Canal and up the coast to Whittier before cycling their way to Cordova and spending the winter there. In the spring, they began the trip north to Talkeetna, where local climbing experts Willi Prittie, Brian Okonek, and Roger Robinson provided insight on the terrain and the best way to get in and out of the Alaska Range without an engine. Dario says the feeling of true wilderness on the way in and out is part of what appeals to him.

"It was a little bit [of] an adventure to get through the willows on the moraine to get to the Kahiltna Glacier, and then it was straight forward. It was so nice, no people, this wonderful mountain surrounding you..."

Once the expedition reached base camp, they begin seeing other people again, and on the way down, there were hundreds of climbers on the mountain. Martin Schuster grew up in Alaska and was part of the Denali climb. He also says that the parts of the trip that were off the beaten path were the most memorable.

"From Petersville up to base camp and from base camp down to Talkeetna, we didn't see anybody. That really made the trip for me. It was really cool just being out in the middle of nowhere without one hundred, two hundred people doing the exact same thing you are."

The Denali climb was successful, but for Dario and Sabine, that's not the most important part of the expedition.

"In Top to Top, on this global climate expedition, we really try to volunteer as much as possible for a good cause and then teach the children and inspire them with all the positive examples we encounter on our journey. That's actually really filling our batteries."

Sabine Schwörer did not climb Denali, since the family's children are too young for the harsh environment. Instead, she stayed behind and conducted homeschooling and other aspects of the expedition. She has been part of the expedition since the first day, back in 2002. She jokes that Dario told her it would only take four years to finish the journey. Twelve years and four children later, she says she is still enjoying the trip.

"I really, really enjoy the time in the classrooms, and working with the children, and how amazing [the] ideas they have [about] what we could do better with our planet. I think it's really important to invest in the children. They are so open, and they still have lots of the future in their hands."

In all, the Top to Top expedition has sailed more than 70,000 nautical miles, and Dario and Sabine have shared their journey with more than 70,000 students in a hundred countries. Their work in local initiatives has helped clean up more than 50,000 tons of waste. They have one continent and one peak left to do, Mount Vinson in Antarctica. They aren't in any particular hurry to get there, though.

"Our idea is to go through the Northwest Passage, so we go again out to the Aleutians and up to Cape Barrow, then through the Arctic to Greenland, then make it down the East Coast of the U.S., through Panama, then to Patagonia again and Antarctica. So what we're trying to do is a figure-eight around the two Americas."

Obviously, that route takes much longer then sailing straight back down the West Coast of North and South America. Dario estimates another three or four years ought to do it. No doubt thousands more children will share in the Schwörer family's one-of-a-kind journey by the time it's over.""